“Virginia?”

“Yes, don’t you see? Virginia is where it will begin. And it is where there are men who will do it. Just as it was Virginia where it all began in the beginning, or at least where the men were to conceive it, the great Revolution, fought, won it, and saw it on its way. They began the Second Revolution and we lost it. Perhaps the Third Revolution will end differently.”

“It won’t be California after all. It will be settled in Virginia, where it started.”

“Virginia!”

—Walker Percy, Lancelot

April Porch Reading

There’s nothing quite like springtime in the South. The gentle sun, blooming color, the relentless chorus of birds, frogs, and insects… it’s all a merciful prelude to the oppression of summer, and the perfect time to do some reading on the porch.

Last month we discussed Mel Bradford’s book, Original Intentions, which explores the painstaking process of ratification. Contrary to popular belief, ratification was not the imposition of a new ideological regime. Rather, despite a broad range of perspectives and interests, the framers ultimately submitted to the settled ways of the past to establish a nomocratic order—a system of fixed rules of procedure without predetermined ends.

Bradford’s argument stands in stark contrast to the teleological view of the American founding, which sees the Constitution advancing a philosophical agenda or achieving a certain kind of society. Today this view has eclipsed all other interpretations, and yet Bradford’s argument is still worth pondering. For if he is right, historical context is far more important than we want to admit, and the Constitution’s meaning is best understood through the intentions of ratifying conventions rather than the individual framers.

Whether you agree or disagree, Bradford’s argument is still useful as it stands in stark contrast to the prevailing view of the American founding and traces the contours of our own teleocratic regime. If our system of government exists to serve a purpose—and just about everyone seems to think so—then substantive goals and outcomes will always be more important than the process by which they are achieved. Moreover, if the Constitution is beholden to a certain philosophical agenda, then virtually any act of subversion in service of that agenda is justifiable.

As Elizabeth Corey points out,

If government itself becomes ‘telocratic’ we have little ability to protest and no real possibility of exit. We are compelled, by force or threat, to take substantive action of a sort that we may or may not approve, all in the service of an end we have not chosen. To paraphrase Oakeshott, there is only one thing worse than hearing the dreams of others, and that is being forced to live them yourself.

When we find ourselves complaining about partisan judges, lawless bureaucrats, or a “toothless” Constitution, we should revisit Bradford’s argument and perhaps consider that the abysmal status quo is not merely the result of bad philosophy or misguided leaders but the systematic breakdown of a nomocratic order. The implications are significant, for it would mean that legitimacy depends on more than just power, authority, or ideological purity.

As the current regime recklessly pursues ideological ends, order continues to deteriorate and the system itself becomes unstable and increasingly hostile to the very people it claims to serve. This is the reality we are living in—anarchy and tyranny reigning side by side.

But assuming Bismark is right that politics is the art of the possible, then Bradford’s argument means that we still have the tools necessary to re-establish order—a way has already been provided. But how do we get there?

With this in mind, I present April’s Porch Reading: Tobacco Culture.

The Tobacco Men

When we recall the great Tidewater planters of the American Revolution—George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Richard Henry Lee, George Mason—we tend to think of them as philosophers and statesmen rather than restless tobacco farmers swept up in the winds of change. Undoubtedly, these men were proud of their political achievements, but they would probably find it perplexing that their agrarian way of life hardly registers in the public imagination. For they were first and foremost crop masters and lords of the soil, proud inheritors of a grand tradition passed down from father to son. The tobacco leaf was the great symbol of their world, and its centrality to their peculiar way of life cannot be overstated. Tobacco cultivation provided them with fabulous wealth, unique privileges, a curious sense of time, a rigid social hierarchy, and a network of value-laden relationships that would eventually spur them to revolt.

At the end of the day, our perception of these men tends to be a distorted reflection of ourselves. Progressive historians at the turn of the century portrayed the Tidewater planters as cold-blooded materialists. The next generation saw them as idealistic scholars and philosophers. And today critical theory has corroded their image to such an extent that they appear crude and almost alien.

But I suspect that the old men of the Tidewater still have much to impart, and a better understanding of their world may help us recognize our own political possibilities today.

Tobacco Culture

In his 1985 book, Tobacco Culture, historian T.H. Breen explores the mentality of the Tidewater planters and the importance of Virginia’s tobacco culture to the American Revolution.

Breen departs from both progressive and idealistic interpretations to argue that tobacco cultivation played a greater role in shaping the temperament and politics of the Tidewater elite than previously understood. Furthermore, this tobacco culture, which gave rise to a unique code of honor and desire for personal independence, ultimately radicalized Virginia’s planters in the 1760s, leading them to embrace the Revolutionary cause.

To make his case, Breen provides a rich description of life in the Tidewater, where the tobacco leaf served as the supreme symbol of honor, friendship, independence, wealth, and, soon enough, politics.

Several themes underscoring the relationship between tobacco cultivation and politics stand out:

The Agrarian Context and Tobacco Mentality

The Tidewater planters were country people with a special connection to the land and its rhythms. These were men bound by rules—not only natural laws of their physical environment but layers of complex social customs as well.

“On one level, tobacco shaped general patterns of behavior. The plant’s peculiar physical characteristics influenced the planters’ decisions about where to locate plantations and how to allocate time throughout the year. In other words, tobacco added a dimension to the colonists’ perceptions of time and space… and contributed powerfully to the development of a tobacco mentality.

On a second level, however, tobacco gave meaning to routine planter activities. It was emblematic not only of a larger social order, its past, its future, its prospects in comparison with those of other societies, but also of the individual producers… there was a crucial psychological link between planter and tobacco. The staple provided the Lees and Carters of mid-eighteenth-century Virginia with a means to establish a public identity, a way to locate themselves within a web of human relations. The crop served as an index of worth and standing in a community of competitive, highly independent growers; quite literally, the quality of a man’s tobacco often served as the measure of the man…”

In such a setting, with the crop and cultivator so inextricably linked, it can be difficult to separate economics from culture; tobacco was, after all, the source of individual and corporate meaning.

Tobacco and Debt

The planters’ role as players in a global market, along with their economic dependence on British merchants, made personal debt a perennial concern. As Breen observes, Tidewater planters great and small were obsessed with debt… enough so that a “culture of debt” emerged.

“Over the course of the eighteenth century, the great tobacco planters—those that produced the largest crops and sent them to the major merchant houses of London, Bristol, and Glasgow on consignment—developed an elaborate mental framework that gave meaning and coherence to commercial transactions, to ongoing exchanges with merchants living thousands of miles away and often involving complex credit arrangements. During the 1760s and 1770s instabilities in the international economy, over which the planters had no control, strained ties between merchant and producer. In these difficult circumstances the language of commerce, which had taken on idiosyncratic overtones in the Virginia context, acquired new meanings to fit changing external conditions. The transformation of how planters perceived their relations with British merchants seemed to undermine the core of the tobacco mentality and thus, especially after 1772, to demand a revolutionary response.”

With such great distance between colony and mother country, the Tidewater planters were forced to interpret the ambitions of merchants and government officials from afar, often assuming benevolent motives like they would a friend. But as economic troubles surfaced, this distance also fueled suspicions of conspiracy and betrayal; an experience that would prime the planters for the revolutionary rhetoric of the 1770s.

It is worth noting that the constant anxiety over debt goes far beyond personal embarrassment or dishonor. As private papers attest, the planters’ fears were far more existential. Mounting debt threatened their very way of life.

By the 1760s, the colonies were experiencing a financial crisis. Trade was slow, cash was scarce, and to make matters worse, the soil in some of the oldest tobacco plantations had been completely depleted; crop failures were high. Some prominent families were forced to abandon tobacco and leave the Tidewater altogether.

By 1769, these debt problems had turned into a full-fledged cultural crisis, threatening the survival of the Tidewater’s traditional social order.

“The planter elite seemed uncertain, as if its position in Virginia society was not as secure as it might once have been. The problems that confronted these men were by no means imaginary. A gradual shift in large sections of the Tidewater away from tobacco to wheat, a change that had commenced in some places in the 1740s and would continue after the Revolution, had seriously begun to undermine the tobacco mentality. Achieving recognition as a crop master was becoming more difficult, and as some planters sank deeper into debt, they simply gave up the effort to produce Virginia’s traditional staple. Neither the transition away from tobacco nor the rising level of indebtedness caused the great planters to support the Revolution. These experiences did, however, help determine how the Tidewater gentlemen ultimately perceived the constitutional issues of the day.”

It would be inaccurate to say that such developments alone drove the Virginia colony to revolution. But tensions between merchants and planters, along with escalating indebtedness in the Tidewater, provided the planters with a personal context in which the revolutionary rhetoric could take hold.

Ultimately, this struggle fostered a political consciousness, leading the planter elite to view their economic situation “in terms of lost virtue, personal betrayal, and possible enslavement” and to take collective steps to protect their friends and families from “scheming” financial interests.

Independence and Revolution

Tidewater planters began to plumb the depths of classical literature for insights and relief, adopting an ancient vocabulary of virtue borrowed from the Romans and Greeks. Many latched onto the radical Country ideology of Lord Bolingbroke, who had railed against conspiracy and corruption in England just decades before. This newfound interest in politics spurred a flood of private correspondence as well, and the lending of books and pamphlets between households was common. Tobacco had always required great diligence and attention to detail, and the planters approached their political activities much in the same way.

When London looked to the colonies to help alleviate its own debt problems, the men of the Tidewater had already embraced the radical politics of the English countryside in their struggle for independence from debt and financial “slavery.” As Breen notes, such experiences gave “moral force to the general Country idioms of the day” and would later prove invaluable.

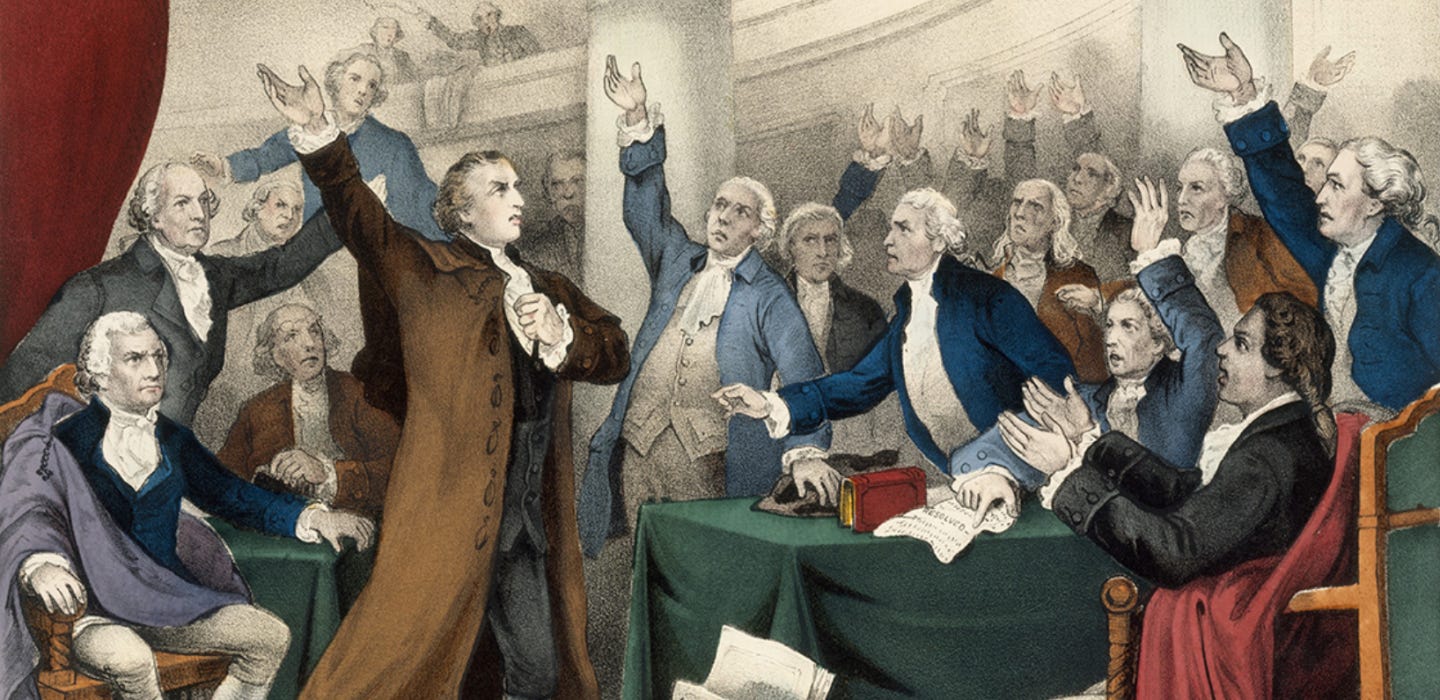

No one embodies this political transformation better than Patrick Henry.

Like other prominent planters, Henry encouraged his peers to guard their personal autonomy by exercising classical virtue. But Henry’s admonitions were not scholarly in the least. Instead, he sounded like a backcountry planter railing against London merchants. It was a familiar battlecry to Virginia’s indebted planters:

“He spoke like an evangelical preacher, his explosive rhetoric cascading over his listeners until all but the most resistant had been swept away. His performances incorporated general idioms of everyday experience. In his reflections upon Henry’s ‘powerful eloquence’ recorded after the Revolution, Edmund Randolph noted, ‘It was enough to feel, to remember some general maxims coeval with the colony.’

In other words, Henry possessed an extraordinary ability to transform individual discontent, much of it inchoate, into a collective issue.”

When Henry attacked the Stamp Act, he did so with the same moral urgency that he used against merchants and the loan office. Merchants and government officials alike had undermined Virginia’s virtue, he insisted, “One act represented an external threat to liberty, the other an internal seed of corruption…”

Henry helped his countrymen see Virginia’s cultural crisis in the starkest terms: a struggle for freedom against financial enslavement and tyrannical power. His rhetoric was always steeped in classical virtues and country idioms, inspiring even the most erudite of his peers—namely, a young Thomas Jefferson—to action.

He exhorted his fellow planters to take collective steps against this double threat. They would need a moral regeneration, beginning with their own households, and with any luck, this reformation of sorts would spread to entire communities. They were to be frugal, resist the temptations of ease and luxury, and jealously guard their liberty—together.

And the rest is history.

Breen concludes:

“By focusing attention upon the cultural, as opposed to the economic significance of debt and tobacco, one begins to understand why these particular planters might have voiced radical Country ideas with such passion during this period. After 1773 the Virginians’ political ideology resonated with meanings drawn from the experiences of everyday life. It gained power through association with an angry commercial discourse. When the great planters spoke of conspiracy or slavery, they were not mouthing abstractions borrowed from the writings of English Country authors. A source of their hyperbole—though perhaps not the only one—can be found in those private disappointments, humiliations, and misunderstandings recounted so poignantly in the letterbooks.”

Tidewater Today

Published nearly 40 years ago, T.H. Breen’s Tobacco Culture remains one of the best historical studies of the Tidewater region and stands alone in showing how culture, commercial interests and ideological beliefs can merge into a single, powerful political movement.

The Tidewater planters we still remember today were not scholars, philosophers, or ideologues. Instead, they were a group of tobacco farmers navigating a unique social reality, where the problems of daily life were sorted out “in the fields and the marketplace.”

The economic burdens they endured, along with the prospect of losing their unique way of life, helped transform their anxieties into a coherent political ideology; one that prized personal independence, honor, and virtue—the humble beginnings of American republicanism. Ultimately, tobacco, debt, and distance would convince them to break with their economic and political system and turn them into revolutionaries. And the fervor and moral clarity they brought to the fight—the product of an endless struggle with foreign creditors—helped America win her independence.

Tobacco Culture is a fascinating look at the symbiotic relationship between experience and ideology, and it invites us to examine the past and present with new eyes. Like the Tidewater planters, we all occupy a unique social reality, with political possibilities that may not reveal themselves yet. Likewise, the complex interactions and dependencies that define even the most mundane details of daily life are worth noticing, for without an appreciation for such things, we cannot begin to understand our own beliefs, values, and ideals, and how they relate to power… we cannot begin to imagine our own political possibilities.

I bought “original intentions. “

You might want to have a look at this book about the contemporary events of the East India Company, of which the Founders were painfully aware.

Certainly alarmed.

The Anarchy by William Dalrymple.

As the Founders were certainly aware of Ireland, although they would have shuddered to mention it, never mind compare.

https://a.co/hm3dXxO

The American Revolution and The East India Company were to influence each other rather dramatically, through the medium of London. In fact the echo back gave us our modern concepts of race, to our lasting confusion.